Deep Learning Part 2 - Restricted Boltzmann Machines and Feedforward Neural Networks

This is the second in a several-part series on the basics of deep learning, presented in an easy-to-read, lightweight format. Here is a link to the first one. Previous experience with basic probability and matrix algebra will be helpful, but not required. Send any comments or corrections to josh@jzhanson.com.

Mathematically, Restricted Boltzmann Machines are derived from the Maxwell-Boltzmann Distribution plus matrix algebra, which we’ll go over in this post. We’ll also use that as a bridge to connect to the basics of neural networks.

The Boltzmann Distribution

Let us first define x to be a vector of n outcomes, where each xi can either be 0 or 1. Of course, each xi can have a different probability of being 1. The probabilities can even be conditional, a la Markov Chains. But more on that later. In the previous post, we have usually thought of x as being a single random variable. Here, however, it is a vector of individual random variables. We are assuming the discrete case here, where each element of a vector can either be 0 or 1.

\[\textbf{x} = \begin{bmatrix} x_1 & x_2 & \ldots & x_n \end{bmatrix}, \: x_i \in \{0, 1\}\]With that definition out of the way, we can examine the Boltzmann distribution, invented by Ludwig Boltzmann, which models a bunch of things in physics, like how a hot object cools, or how energy dissipates into the environment. We have

\[p(x) = \frac{1}{Z} \exp (-E(\textbf{x})), \: E(\textbf{x}) = - \textbf{x}^T \textbf{U} \textbf{x} - \textbf{b}^T \textbf{x}\]Here, Z is the partition function or normalizing constant which makes sure that the distribution sums to one. It has actually been proven that the partition function Z is intractable, which means that it cannot be efficiently solved or evaluated. This is not hard to see, because Z requires calculating all combinations of xs, and if x has n elements, then we have 2n possibilities.

The exp function is the same as raising the constant e to the function’s argument, which is the energy function. Within the energy function, we have a U, which is the matrix of weights that our variable x interacts with, and a b is the vector of biases for each x. For now, let’s force U to be symmetric.

If we expand the first matrix multiplication term,

\[\textbf{x}^T \textbf{U} \textbf{x} = \begin{bmatrix} x_1 & x_2 & \ldots & x_n \end{bmatrix} \Bigg[ \textbf{u}_1 \quad \textbf{u}_2 \quad \ldots \quad \textbf{u}_n \Bigg] \begin{bmatrix} x_1 \\ x_2 \\ \vdots \\ x_n \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \textbf{x}^T \textbf{u}_1 & \textbf{x}^T \textbf{u}_2 & \ldots & \textbf{x}^T \textbf{u}_n \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} x_1 \\ x_2 \\ \vdots \\ x_n \end{bmatrix}\]Which we observe is a scalar, since each xTui is a scalar.

RBMs

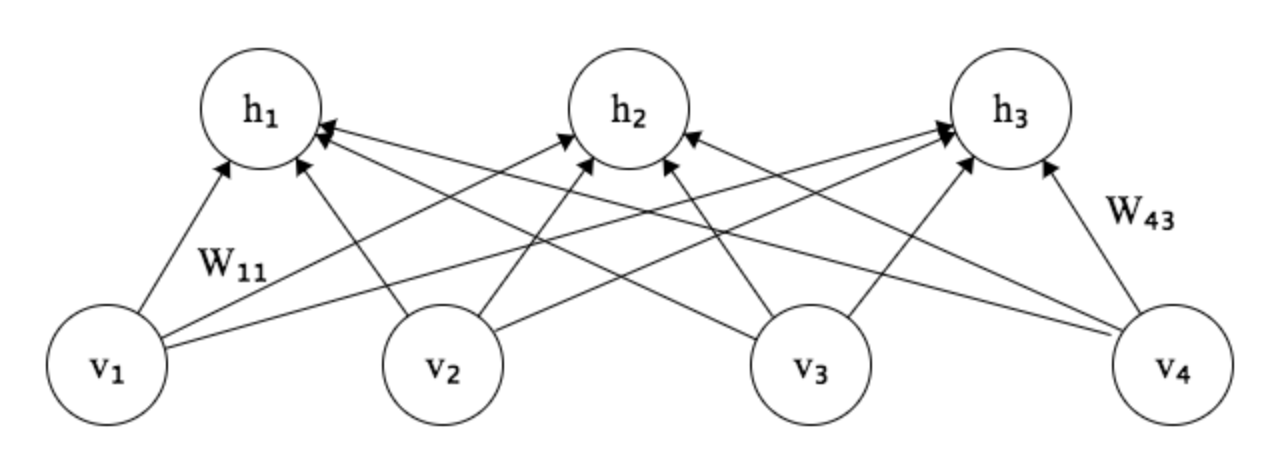

To formally define a Restricted Boltzmann Machine (referred to as a RBM), we need to make a couple things clear. So far, we’ve thought of the input to the energy function, the vector x, as our observations or samples from the distribution. RBMs switch that up a little - they assume that the state vector x is composed of two parts: some number of visible variables v, and some number of hidden variables h.

\[\textbf{x} = (\textbf{v}, \textbf{h})\]Why do we explicity split x into the visible and hidden variables? It turns out that modeling the interaction between visible and hidden variables is very powerful - in fact, by modeling these interactions and stacking RBMs, we can do a lot of cool things.

We can then rewrite the energy function:

\[E(\textbf{v}, \textbf{h}) = - \begin{bmatrix} \textbf{v}^T & \textbf{h}^T \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \textbf{R} & \frac{1}{2}\textbf{W} \\ \frac{1}{2}\textbf{W}^T & \textbf{S} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \textbf{v} \\ \textbf{h} \end{bmatrix} - \begin{bmatrix} \textbf{b}^T \\ \textbf{c}^T \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \textbf{v} & \textbf{h} \end{bmatrix}\]Note that we have decomposed U into four quarters, which are themselves matrices and which we compose out of matrices we name R, W, and S, and we have decomposed bT into bT and aT, which are the respective parts of the bias matrix that are multiplied by v and h. Because U is symmetric, the upper-right and lower-left quarters must be each other’s transpose. We name them 1/2 W instead of just W for reasons that will become clear once we expand the first matrix multiplication:

\[\begin{bmatrix} \textbf{v}^T & \textbf{h}^T \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \textbf{R} & \frac{1}{2}\textbf{W} \\ \frac{1}{2}\textbf{W}^T & \textbf{S} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \textbf{v} \\ \textbf{h} \end{bmatrix}\] \[= \begin{bmatrix} \textbf{v}^T \textbf{R} + \frac{1}{2} \textbf{h}^T \textbf{W}^T & \frac{1}{2} \textbf{v}^T \textbf{W} + \textbf{h}^T \textbf{S} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \textbf{v} \\ \textbf{h} \end{bmatrix}\] \[= \textbf{v}^T \textbf{R} \textbf{v} + \frac{1}{2} \textbf{h}^T \textbf{W}^T \textbf{v} + \frac{1}{2} \textbf{v}^T \textbf{W} \textbf{h} + \textbf{h}^T \textbf{S} \textbf{h}\]and by applying the property of matrix multiplication that (AB)T = BTAT on the second term, we have

\[\textbf{h}^T \textbf{W}^T \textbf{v} = (\textbf{W} \textbf{h})^T \textbf{v} = [\textbf{v}^T (\textbf{W} \textbf{h})]^T = \textbf{v}^T \textbf{W} \textbf{h}\]The last equality is because the triple matrix multiplication results in a scalar value and the transpose of a scalar value is the scalar value. Therefore,

\[E(\textbf{v}, \textbf{h})= - (\textbf{v}^T \textbf{R} \textbf{v} + \textbf{v}^T \textbf{W} \textbf{h} + \textbf{h}^T \textbf{S} \textbf{h}) - (\textbf{b}^T \textbf{v} + \textbf{a}^T \textbf{h})\]We can actually see that R models the interactions among visible variables and S models the interactions among hidden variables. If we ignore those two matrix multiplication terms and focus only on the interactions of visible variables with hidden variables, we have the modified energy function

\[E(\textbf{v}, \textbf{h})= - \textbf{v}^T \textbf{W} \textbf{h} - \textbf{b}^T \textbf{v} - \textbf{a}^T \textbf{h}\]which is the basis of a Restricted Boltzmann Machine - the difference between an RBM and a normal Boltzmann Machine is we forget about the visible-visible and hidden-hidden interactions and only concern ourselves with the visible-hidden interactions.

Conditional Derivation

With our new energy function, we can write the joint distribution of v and h for a RBM. Here comes the really cool stuff.

\[P(\textbf{v}, \textbf{h}; \theta) = \frac{1}{Z(\theta)} \exp (-E(\textbf{v}, \textbf{h}; \theta)) \quad \text{where} \quad Z(\theta) = \sum_\textbf{v} \sum_\textbf{h} \exp(-E(\textbf{v}, \textbf{h}; \theta))\]The following derivation of the conditional distribution of h is an expansion of the derivation found in the first couple pages of Ruslan Salakhutdinov’s PhD thesis, so I use the same notation here, where theta is W, b, and a, and the semicolon stands for “given” or “dependent upon” while the commas denote parameters of the joint distribution.

Because we’re working in the discrete case, we say that v and h are D and F dimensional vectors, all of elements that can be either 0 or 1.

\[\textbf{v} \in \{0, 1\}^D \quad \text{and} \quad \textbf{h} \in \{0, 1\}^F\]We aim to find the conditional distribution of h given v, because that would allow us to model the distribution of the hidden variables given values of visible variables. We can start by applying Bayes’ Rule to rewrite the conditional in terms of the joint, which we have above, and the marginal on the denominator, which we will proceed to derive.

\[P(\textbf{h} \vert \textbf{v}; \theta) = \frac{P(\textbf{v}, \textbf{h}; \theta)}{P(\textbf{v}; \theta)}\]To derive the marginal, we take the joint distribution on v and h and sum over all values of h and expand, replacing matrix multiplication terms with sigma notation.

\[P(\textbf{v}; \theta) = \sum_h P(\textbf{v}, \textbf{h}; \theta) = \frac{1}{Z(\theta)} \sum_h \exp (-E(\textbf{v}, \textbf{h}; \theta))\] \[= \frac{1}{Z(\theta)} \sum_h \exp (-(- \textbf{v}^T \textbf{W} \textbf{h} - \textbf{b}^T \textbf{v} - \textbf{a}^T \textbf{h}))\] \[= \frac{1}{Z(\theta)} \sum_h \exp (\sum_{i = 1}^D \sum_{j = 1}^F v_i W_{ij} h_j + \sum_{i = 1}^D b_i v_i + \sum_{j = 1}^F a_j h_j)\]We can bring out the bi vi term out of the exp and the outer summation as a product, because ea + b = ea eb.

\[= \frac{1}{Z(\theta)} \cdot \exp(\sum_{i = 1}^D b_i v_i) \cdot \sum_h \exp (\sum_{i = 1}^D \sum_{j = 1}^F v_i W_{ij} h_j + \sum_{j = 1}^F a_j h_j)\]We can also swap the double summations in the latter exp as well as pull out the hj, because it only depends on j and not i, and then pull out the j = 1 to F summation.

\[= \frac{1}{Z(\theta)} \cdot \exp(\sum_{i = 1}^D b_i v_i) \cdot \sum_h \exp (\sum_{j = 1}^F ( \sum_{i = 1}^D v_i W_{ij}) h_j + \sum_{j = 1}^F a_j h_j)\] \[= \frac{1}{Z(\theta)} \cdot \exp(\sum_{i = 1}^D b_i v_i) \cdot \sum_h \exp \Big[ \sum_{j = 1}^F ( ( \sum_{i = 1}^D v_i W_{ij}) h_j + a_j h_j) \Big]\]Just like we did above, we can use the fact that ea + b = ea eb to pull out the j = 1 to F summation out of the exp and turn it into a product.

\[= \frac{1}{Z(\theta)} \cdot \exp(\sum_{i = 1}^D b_i v_i) \cdot \sum_h \exp \Big[ \sum_{j = 1}^F (( \sum_{i = 1}^D v_i W_{ij}) h_j + a_j h_j) \Big]\] \[= \frac{1}{Z(\theta)} \cdot \exp(\sum_{i = 1}^D b_i v_i) \cdot \sum_h \prod_{j = 1}^F \exp ((\sum_{i = 1}^D v_i W_{ij}) h_j + a_j h_j)\]Now it seems fairly intuitive that you can switch the product and the sum, especially if we remember that each hj must be either 0 or 1. Indeed, if we simply take the two cases which hj can be and plug in hj = 0 (which cancels everything out and exp(0) = 1) and hj = 1, we arrive at

\[= \frac{1}{Z(\theta)} \cdot \exp(\sum_{i = 1}^D b_i v_i) \cdot \prod_{j = 1}^F \sum_{h_j \in \{0, 1 \}} \exp ((\sum_{i = 1}^D v_i W_{ij}) h_j + a_j h_j)\] \[= \frac{1}{Z(\theta)} \cdot \exp(\sum_{i = 1}^D b_i v_i) \cdot \prod_{j = 1}^F (1 + \exp (\sum_{i = 1}^D v_i W_{ij} + a_j))\]If you’re willing to take this on faith, skip the next subheading and go to Plugging in. If you would like a detailed explanation of why this is true, read on!

Expansion of the product-sum

To formally derive that

\[\sum_h \prod_{j = 1}^F \exp ((\sum_{i = 1}^D v_i W_{ij}) h_j + a_j h_j) = \prod_{j = 1}^F (1 + \exp (\sum_{i = 1}^D v_i W_{ij} + a_j))\]Let’s define a function as follows:

\[f(j, h_j; \theta) = \exp ((\sum_{i = 1}^D W_{ij} v_i) h_j + a_j h_j)\]for our hidden variable vector,

\[\textbf{h} = \begin{bmatrix} h_1 & h_2 & \ldots & h_F \end{bmatrix}, h_j \in \{ 0, 1 \}\]Note that

\[f(j, 0; \theta) = 1 \quad \text{and} \quad f(j, 1; \theta) = \exp (\sum_{i = 1}^D W_{ij} v_i + a_j) \quad \forall j\]Therefore, the whole product is equal to evaluating the product on a subset of the terms where \(h_j = 1\).

\[\prod_{j = 1}^F f(j, h_j; \theta) = \prod_{j \in \{i_1, \ldots, i_k \}} f(j, 1; \theta) \quad \text{where} \quad h_j = 1, \: j \in \{ i_1, i_2, \ldots, i_k \}\]We want to make statements and write equations about all vectors of this type. For any vector of this type, it has \(k\) ones. Because they’re \(F\)-dimensional, that means that there \(F - k\) zeroes. The ones can be distributed in any fashion - evidently, summation notation is insufficient, and adding combinations into the mix won’t strengthen the concept…how about we use an uppercase kappa, standing for “k-combinations of products” in the same vein as the uppercase sigma for sum and pi for product? Another option: lowercase nu, which looks like a \(\nu\)?

Hereafter, we denote “sum across all vectors h with dimension F and from k = 0 to F ones” as

\[\underset{j \in \{i_1, \ldots, i_k \} }{K}\]In any case, we can write that the latter portion of the equation up there with this new function f and our new notation as

\[\underset{j \in \{i_1, \ldots, i_k \} }{K} f(j, h_j; \theta)\]which is summing over all vectors h with 0 to F ones and all other zeroes \(f(j, h_j; \theta\), where j is the vector element index and hj is the element at that index, and multiplying them together - the product \(\prod_{j = 1}^F\) is included in the kappa notation.

To expand it and make it a little less abstract, we have

\[= \big[ f(1, 0; \theta) f(2, 0; \theta) \ldots f(F, 0; \theta) \big]\] \[+ \big[ f(1, 1; \theta) f(2, 0; \theta) \ldots f(F, 0; \theta) + f(1, 0; \theta) f(2, 1; \theta) \ldots f(F, 0; \theta) + \ldots + f(1, 0; \theta) f(2, 0; \theta) \ldots f(F, 1; \theta) \big]\] \[+ \ldots\] \[+ \big[ f(1, 1; \theta) f(2, 1; \theta) \ldots f(F, 1; \theta) \big]\]where between each set of square brackets is all vectors h with k = 0, k = 1, and k = F ones. There is one vector each for k = 0 and k = F and there are F vectors for k = 1, and F choose two vectors for k = 2, and so on.

Now here’s our doozy: because all \(f(j, 0; \theta)\) turn into ones, we can actually factor the entire expression into

\[= \prod_{j = 1}^F (1 + \exp (\sum_{i = 1}^D W_{ij} v_i + a_j))\]It might be a bit easier to see with an example. Let’s factor the two dimensional case, F = 2 with the four vectors \(\textbf{h} = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix}, \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} , \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} , \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 \end{bmatrix}\)

We have

\[\underset{j \in \{i_1, i_2 \} }{K} f(j, h_j; \theta) = f(0, 0) f(1, 0) + \big[ f(0, 1) f(1, 0) + f(0, 0) f(1, 1) \big] + f(0, 1) f(1, 1)\] \[= 1 + 1 \cdot f(0, 1) + 1 \cdot f(1, 1) + f(0, 1) f(1, 1) = (1 + f(0, 1))(1 + f(1, 1)) = \prod_{j = 1}^2 (1 + f(j, 1))\] \[= \prod_{j = 1}^2 (1 + \exp (\sum_{i = 1}^D W_{ij} v_i + a_j))\]which seems like a whole lot of ado for what could have been a simple expansion, but I found this to be a neat math trick :).

Plugging in

Now that we have expanded the marginal, we can actually note that because we don’t actually manipulate the summation over all h except the last part, we can similarily expand the joint distribution \(P(\textbf{v}, \textbf{h}; \theta)\) using the same steps.

\[P(\textbf{h} \vert \textbf{v}; \theta) = \frac{P(\textbf{v}, \textbf{h}; \theta)}{P(\textbf{v}; \theta)} = \frac{\frac{1}{Z(\theta)} \exp (-E(\textbf{v}, \textbf{h}; \theta))}{P(\textbf{v}, \theta)}\] \[= \frac{\frac{1}{Z(\theta)} \exp (\sum_{i = 1}^D \sum_{j = 1}^F v_i W_{ij} h_j + \sum_{i = 1}^D b_i v_i + \sum_{j = 1}^F a_j h_j)}{P(\textbf{v}, \theta)}\] \[= \frac{\frac{1}{Z(\theta)} \exp (\sum_{i = 1}^D b_i v_i) \cdot \exp (\sum_{j = 1}^F \sum_{i = 1}^D v_i W_{ij} h_j + \sum_{j = 1}^F a_j h_j)}{P(\textbf{v}, \theta)}\] \[= \frac{\frac{1}{Z(\theta)} \exp (\sum_{i = 1}^D b_i v_i) \cdot \prod_{j = 1}^F \exp ((\sum_{i = 1}^D v_i W_{ij}) h_j + a_j h_j)} {\frac{1}{Z(\theta)} \exp (\sum_{i = 1}^D b_i v_i) \cdot \prod_{j = 1}^F (1 + \exp(\sum_{i = 1}^D W_{ij} v_i + a_j))}\]Cancelling terms and pulling out the product,

\[= \prod_{j = 1}^F \frac{\exp ((\sum_{i = 1}^D v_i W_{ij}) h_j + a_j h_j)}{1 + \exp(\sum_{i = 1}^D W_{ij} v_i + a_j)}\]which we can write as the element-wise conditional

\[= \prod_{j = 1}^F P(h_j \vert \textbf{v}; \theta) \quad \text{where} \quad P(h_j \vert \textbf{v}; \theta) = \frac{\exp ((\sum_{i = 1}^D v_i W_{ij}) h_j + a_j h_j)}{1 + \exp(\sum_{i = 1}^D W_{ij} v_i + a_j)}\]Now we make the step that takes the cake. We care about the conditional probability that hj = 1, and when we set hj = 1, we actually see that the distribution turns into the sigmoid function!

\[P(h_j = 1 \vert \textbf{v}; \theta) = \sigma (\sum_{i = 1}^D W_{ij} v_i + a_j) \quad \text{where} \quad \sigma(x) = \frac{\exp (x)}{1 + \exp (x)}\]And now we have shown a mathematical theoretical basis for why the units in a neural network carry a nonlinearity - oftentimes, the sigmoid function, as the activation function. It corresponds exactly to the conditional probability that the hidden variable is 1. What’s the sigmoid function dependent on? The sum of every visible variable - which can be 0 or 1 depending on whether each visible unit “fired” or not - times its appropriate weight plus the bias for that hidden unit.

Moreover, we’ve actually derived the architecture of vanilla neural networks from the mathematical structure of Restricted Boltzmann Machines, where some number of visible units all feed into each hidden unit, where their connections are multiplied by weights and biases are added within each unit and the sigmoid function is applied to determine whether the output of that unit will be 1 or 0. That is, whether the “neuron” will “fire” or not.

Thanks to Evan Wallace’s Finite State Machine Designer.

Most of these distributions in statistics and machine learning are taught because they work - the Boltzmann Distribution, for example, is notable because it does a good job of modeling natural phenomena. Many many distributions and methods are lost because, while mathematically novel, they aren’t useful. The ones we do remember are the ones that work, the ones that fit phenomena or predict well.

The difference between RBMs and feedforward neural networks is that RBMs are a probabilistic model while feedforward neural networks are deterministic. We just take the mean of the first conditional distribution p(hj | v) to get our deterministic neural networks. We can also go from discrete, where our inputs and outputs can only be 0 or 1, to continuous, where inputs and outputs can take any value from 0 to 1, but we have to add some restrictions and flip some signs around - the energy function has to have all its signs reversed and the weights matrix U has to be positive definite for the distribution to converge and integrate to 1.

Again, we have just shown that there’s a theoretical foundation for neural networks. It was actually this proof, combined with Hinton’s discovery that stacking RBMs - in much the same fashion as we now stack layers of hidden units to form deep neural networks - yielded promising results in feature extraction, discrimination/classification, object detection, and many other classes of tasks actually kicked off the boom in AI and deep learning that we’re seeing now. We’ve just shown the basis of all that.

Pretty cool.