Deep Learning Part 1 - Bayes' Rule and Maximum Likelihood

This is the first in a several-part series on the basics of deep learning, presented in an easy-to-read, lightweight format. Previous experience with basic probability and matrix algebra will be helpful, but not required. Send any comments or corrections to josh@jzhanson.com.

Bayes’ Rule

We begin our discussion with Bayes’ rule, an important result that captures the intuitive relationship between an event and prior knowledge we have of factors that might affect the probability of the event. Simply put, it formulates how event B affects the probability of event A. It forms the basis of Bayesian inference and Naive Bayes. Because it is a little difficult to grasp intuitively at first, let’s go over its derivation from the definition of conditional probability, which is easier to understand at first.

Conditional probability

Conditional probability simply formulates the probability of event A happening given that event B happened.

\[P(A \vert B) = \frac{P(A \cap B)}{P(B)} \text{ or, equivalently, } P(B \vert A) = \frac{P(B \cap A)}{P(A)}\]The Ps basically mean “probability of,” the vertical bar | on the left side simply means “given,” and the little upside-down u on the numerator of the right side means “and,” as in event A happening and event B happening.

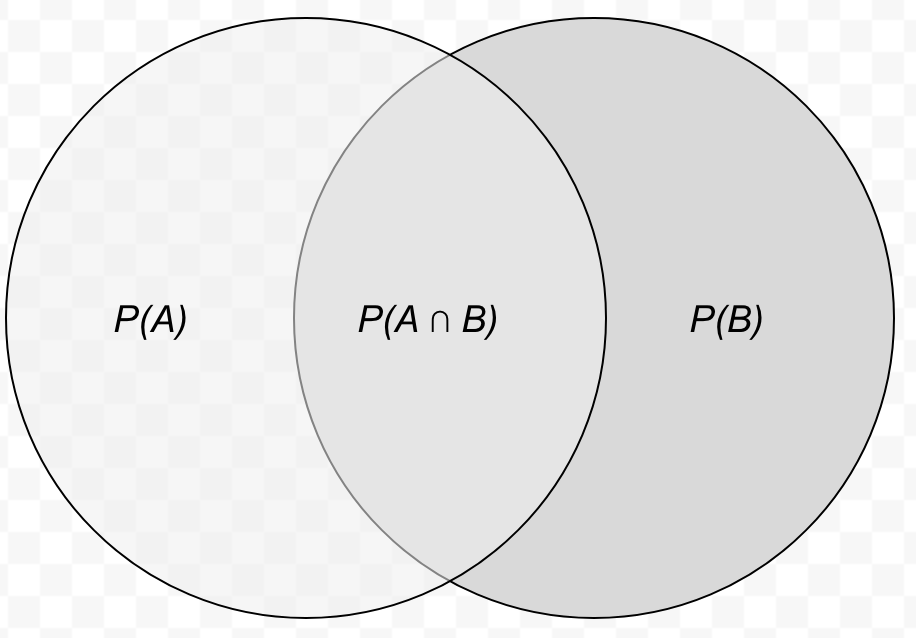

What conditional probability is saying is that the probability of event A given event B is equal to the probability of event A and event B happening divided by the probability of event B. It’s a bit easier to see with a Venn diagram of probabilities.

It is fairly clear that if we assume that event B happens and we wish to consider the probability of event A happening, then we only need to consider the probability space where B happens, that is, the right, darker circle P(B). Within that circle, there’s the middle section, P(A and B), which is how A can happen if we assume that B happens. So we can see that the probability of A given B is equal to the probability of A and B (how A can still happen given that B happens) divided by the total probability space under consideration, P(B), because, again, we’re assuming that B happens.

\[\implies P(A \vert B) P(B) = P(A \cap B) \text{ and } P(B \vert A) P(A) = P(B \cap A)\] \[\implies P(A \vert B) P(B) = P(B \vert A) P(A)\] \[\implies P(A \vert B) = \frac{P(B \vert A) P(A)}{P(B)}\]We first multiply the denominators on both formulas, set the two formulas equal, because “and” is communative - A and B happening is the same as B and A happening - and finally divide P(B) over, assuming that that probability is not zero, we can easily derive Bayes’ Rule.

Generalizing Bayes’ Rule

\[P(A \vert B) = \frac{P(B \vert A) P(A)}{P(B)}\]We use the Law of Total Probability, which states the probability of any event A is equal to the probability of that event A happening given some event B happening times the probability that B happens, plus the probability of that event A happening given some event B happening times the probability B doesn’t happen. To refer to the diagram above, we’re basically saying that the probability of A is equal to the dark middle portion, A happening given B happening, plus the lightest shaded portion, A happening but B not happening. Notationally, the bar above the letter of an event just means the complement of that event - i.e. the event of that event not happening.

\[P(A) = P(A \vert B) P(B) + P(A \vert \overline{B}) P(\overline{B})\]Let’s use the example of flipping two coins and want to find the probability that the second one is heads. Then, we have

\[P(\text{second coin is heads}) = P(\text{second coin is heads } \vert \text{ first coin is heads}) P(\text{first coin is heads})\] \[+ P(\text{second coin is heads } \vert \text{ first coin is not heads}) P(\text{first coin is not heads})\]We rewrite Bayes’ rule as follows using the Law of Total Probability, replacing the denominator:

\[P(A | B) = \frac{P(B | A) P(A)}{P(B | A) P(A) + P(B | \overline{A}) P(\overline{A})}\]This is for the two variable case, but it is not difficult to see that it generalizes to any finite number of variables, say, if several outcomes partition the sample space, which means that exactly one of these events must happen. So, instead of just having two outcomes, B or not B, we have several. For example, the event of getting a one, a two, a three, a four, a five, or a six when rolling a dice are events that partition the sample space, because exactly one must happen when you roll the dice! The takeaway is that we can write in the general case, with multiple events B1, B2, …, Bn, that

\[P(B_i | A) = \frac{P(A | B_i) P(B_i)}{P(A | B_1)P(B_1) + \ldots + P(A | B_n) P(B_n)}\] \[= \frac{ P(A | B_i) P(B_i)}{\sum^n_{j = 1} P(A | B_j)P(B_j)}\]Now if we leave behind discrete probability and move to continuous probability, not too much changes besides we switch the summation to an integral and swap around some function notation, which we will introduce here. Note that the lowercase ps and fs mean more or less the same thing as the uppercase Ps - they stand for the probability mass or probability density functions for discrete and continuous random variables, respectively. We usually use Greek letters, like theta, to stand for hypotheses, or unknown parameters. We will usually use little English letters, like x, to represent observations, or data values. Don’t worry too much about whey there’s a p here or an f there, it’s just to make a distinction between marginal and conditional or joint distributions. Elsewhere, the notation may vary.

\[p(\theta \:| \: x) = \frac{f(x \: | \: \theta) \, p(\theta)}{\int f(x \: | \: \theta) \, p(\theta) \, d\theta}\]In the context of machine learning, x is the observation - what we sample from some unknown distribution that we want to model. Theta is the unknown parameter that our distribution depends upon, representing our hypothesis on a random variable under observation. Once we know theta, we can easily generate new observations to form a prediction on our random variable under observation. This is why we want to guess at what theta can be as best as we can so we can get a good prediction from the distribution. In fact, each term in the above equation has a name.

The numerator of the left side has f(x | theta), which we refer to as the likelihood, because it’s the likelihood that we observe x if we fix some parameter value theta. We also have a p(theta), which we call the prior, because it usually represents our prior knowledge of theta and how it’s distributed - we have some prior knowledge of how theta behaves and which values it’s likely to take. On the denominator of the right side, we have an integral over all values of theta of the likelihood times the prior, which we can see is just generalizing the Law of Total Probability to the continuous case. We refer to this as the evidence, because it’s what we know about the conditional distribution, f(x | theta), and the prior, p(theta). We can also call the denominator the marginal, because when we integrate across all values of theta, the denominator becomes a function of x only, p(x), which is the total probability. Finally, we call the p(theta | x) on the left side of the equation the posterior distribution, because it’s the distribution we can infer after we combine the information we have from likelihood and the prior and apply Bayes’ Rule. We can rewrite this, with words, as

\[\textbf{posterior} = \frac{\textbf{likelihood} \times \textbf{prior}}{\textbf{evidence}}\]Note that we can easily replace the single value x with a bolded x, representing a vector of multiple values.

\[f(x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_n, \theta) = f(\textbf{x}, \theta)\]Chain rule for conditional probability

In a nutshell, the chain rule for conditional probability states that the probability of a bunch of things all happening is the probability of one of the things happening given the other things happen times the probability of all the other things happening.

\[P(A_1 \cap A_2 \cap \ldots \cap A_n)\] \[= p(A_1, A_2, \ldots, A_n) = p(A_1 | A_2, \ldots, A_n) \times p(A_2, \ldots, A_n)\]The first line of the above is just to illustrate the change in notation, from the “cap” notation earlier to using commas to denote events all happening. We can repeatedly apply the chain rule, giving us

\[= p(A_1 | A_2, \ldots, A_n) \times p(A_2 | A_3, \ldots, A_n) \times p(A_3, \ldots, A_n)\] \[= ...\] \[= p(A_1 | A_2, \ldots, A_n) \times p(A_2 | A_3, \ldots, A_n) \times \ldots \times p(A_{n-1} | A_n) \times p(A_n)\]Likelihood functions

Now if we sample, say, n samples from our unknown distribution, and the assumption here is that the samples are independent, then what we can do is if we know the likelihood function f(xi | theta) and we want to find the probability that theta is a particular value given all our sampled data, we can repeatedly apply the chain rule of probabilities, replacing p with f since we are often dealing with continuous rather than discrete data:

\[f(x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_n, \theta) = f(x_1 | x_2, \ldots, x_n, \theta) \times f(x_2, \ldots, x_n, \theta)\] \[= \ldots\] \[= f(x_1 | x_2, \ldots, x_n, \theta) \times f(x_2 | x_3, \ldots, x_n) \times \ldots \times f(x_n | \theta)\]Note that we don’t have a f(theta) at the end despite the chain rule expansion, because theta is not jointly distributed with the xs.

And finally, because we assume each xi is independent, we can drop all the other xj terms from each conditional probability distribution. This is because they’re independent - i.e. the probability of xi being what it is does not at all depend on what value any other xj takes. This means that we have

\[= f(x_1 | \theta) \times f(x_2 | \theta) \times \ldots \times f(x_n | \theta)\] \[= \prod^n_{i = 1} f(x_i | \theta) = L(\theta | x_1, \ldots, x_n)\]which we call the likelihood function. Note that because the training data, or features, we observed, x1, …, xn, are fixed with respect to theta, the likelihood function is only a function of theta, the unknown parameter upon which our mystery distribution depends. In fact, it is exactly the probability that we observe what we observed, x1, …, xn, given that value of theta. In other words, you can give me a value for theta, and I can use this likelihood function to tell you how likely that we get out the training data x1, …, xn.

Note also that I don’t require a concrete value for theta to construct the likelihood function - I only need some training data x1, …, xn. So, if I wanted to model a particular, unknown, black-box distribution, I sample n samples from it, which I call my training data. I use this training data and the chain rule of conditional probability to construct my likelihood function. I then try to maximize that likelihood function with respect to theta. That is, I try to find the value of theta that gives me the highest likelihood for my observation.

\[\text{argmax}_{\theta \in \Theta} L(\theta | x_1, \ldots, x_n) = \hat{\theta}_{MLE}\]We call the theta that gives us the highest probability from our likelihood function theta-hat - there exist more formal terms for it, but the carat that is used to signify a best-guess estimate looks like a hat. This is known as maximum likelihood estimator, hence the subscript MLE.

We make the distinction that the estimator is the function itself, and the estimate is the estimator evaluated with some observation.

Now that I have an estimated distribution, I can ask the real mystery distribution for some more data samples, known as the test data. If, for each test data point, my estimated distribution says there’s a high probability that I would get this particular point, then I say that my model generalizes well. If my estimated distribution has difficulty distinguishing this test data from, say, garbage data, then I say it generalizes poorly, perhaps suffering from overfitting. Maybe we picked an insufficient functional form, one that isn’t capable of modeling what’s really going on. More on that in future posts.

Conclusion

To summarize, we began by explaining how conditional probability is the basis of Bayes’ Rule, how the chain rule of conditional probability makes a likelihood function, and how to use the likelihood function to find the parameter of a mystery distribution.