Algorithms - Selection

Welcome to the second of a series where I write a bit about an interesting algorithm I learned. Send comments or corrections to josh@jzhanson.com.

This week, we’ll be going over a problem similar to last week’s median of two sorted arrays - finding the kth-smallest element in an unsorted array! This problem is taken from the first lecture of 15-451 Algorithm Design and Analysis at CMU this semester - which happened today. I thought the algorithms that were presented were cool and worth writing a post about.

Note: in this post, the algorithms will be all sequential - therefore, the work equals the span.

Second note: I’m considering whether or not to use LaTeX in some parts - it adds mathematical precision and rigor but it makes the tone of the post a little too formal.

The problem

Let’s define terms first. Say we have a sorted array of elements, not necessarily consecutive. We define an element’s rank to be its position in the sorted array, starting from 1. For example, if we have the array [1, 3, 6, 7, 14, 20, …], the element 1 has rank 1, the element 3 has rank 2, the element 6 has rank 3, and so on.

Our problem: given an unsorted array A of length n and an integer k, find the kth-smallest element. Note that we can find the median of this unsorted array by taking the element with rank n/2 if n is even and n/2 + 1 if n is odd. Also, if the array is sorted, then the kth smallest element is trivially the element with index k.

It is important to always precisely state the input and output of the problem - it helps understand what the problem is asking and prevent you from solving an adjacent but different problem.

Input: An array A of n unsorted data elements with a total order (which just means that the elements can always be compared against each other and “greater” “less” and “equal” are defined), and an integer k in the range 1 to n, inclusive.

Output: The element of A with rank k.

Algorithm #1: Quick select

If we look at the problem, we see that it bears some resemblence to quicksort - in fact, whenever the sorted-ness of an array is mentioned in a problem, a good starting point will be to think about different sorting algorithms - selection sort, insertion sort, mergesort, quicksort, and maybe heap sort or radix/bucket sort if you know extra information about the elements.

In particular, let’s think about quicksort, which is sequential - thinking about mergesort won’t go too far in this case, because after we split the array, we only care about the half that the median is in. In addition, we can’t make any assumptions about the elements in the subarrays after we split in mergesort, while in quicksort we know that the elements in each half of the array are less than the pivot element. We’ll be looking at randomized quicksort, which means that instead of always picking the “middle” index or the “first” index, we pick an element uniformly at random from the array to be the pivot.

Here’s the quicksort algorithm and pseudocode:

-

Pick a pivot element x from the array uniformly at random.

-

Put elements that are less than or equal to x before it and elements that are greater than x after it. Let L be the subarray of elements before x and R be the subarray of elements after x.

-

Recursively call quicksort on L and R.

Note that while quicksort (and the other algorithms presented in this post) work fine with duplicate elements, it simplifies our discussion a little to assume all elements in A are distinct.

def quicksort(A):

if |A| is 1:

return A

x = uniformly random element of A

L = all elements of A less than x

R = all elements of A greater than x

L' = quicksort(L)

R' = quicksort(R)

return L' + x + R'

The bars around an array stand for “length of” that array.

We can make an observation here that lets us adapt this algorithm for finding the kth element. We actually know the lengths of L and R. This means that we can recursively call the algorithm on the subarray that the kth element falls in, and if we are recurring into the left array then we leave k as is but if we are recurring into the right array then we subtract the length of the left array from k.

Specifically, if there are k elements or more in L, we know the element of rank k lies in L. If there are less than k-1 elements in L, then the element of rank k lies in R. We can additionally say that if there are exactly k-1 elements in L, then x is the element of rank k and we’re done!

def quickselect(A, k):

if |A| = 1:

return A[1]

x = uniformly random element of A

L = all elements of A less than x

R = all elements of A greater than x

if |L| == k-1:

return x

else if |L| >= k:

return quickselect(L, k)

else:

return quickselect(R, k-|L|)

Runtime analysis

Let’s do some runtime analysis! Runtime in this context is number of comparisons. We aim to show the entire algorithm has expected runtime O(n).

Informally:

It takes linear O(n) time to construct L and R, since we have to walk through the array and put each element into either L or R. The recursive call is either on the larger side or the smaller side, but we can simplify our worst-case analysis by forcing the recursive call to always be on the larger half.

Because there’s a 1/n chance that each of the n elements is chosen, and each element has a different rank that makes the larger half of size n-1, n-2, …, n/2, n/2, n/2 + 1, …, n-1, (note how the size of the larger half wraps around and gets larger after n/2) this means, along with our inductive hypothesis that it takes some constant d times n runtime which we assume to be true for all values less than n

Formally, we have the recurrence

\[T(n) = cn + E[T(\text{larger side})], \; T(1) = 1\] \[= cn + \frac{1}{n} T(n-1) + \ldots + \frac{1}{n} T(\frac{n}{2}) + \frac{1}{n} T(\frac{n}{2}) + \ldots + \frac{1}{n} T(n - 1)\] \[= cn + \frac{2}{n} \sum_{i = \frac{n}{2}}^{n - 1} T(i)\] \[= cn + \frac{2}{n} (d(n - 1) + d(n - 2) + \ldots + d(\frac{n}{2}))\] \[= cn + \frac{3}{4} dn \leq dn \quad \text{if} \quad d = 4c\]Of course, it is unlikely that writing and solving a recurrence will be required in anything other than an academic setting. Note also that our O(n) runtime in expectation, which means that we could have worse runtime (namely, O(n2) runtime if we consistently pick bad or the worst element, just like in quicksort, but this is unlikely.

Algorithm #2: Median of medians

While the above quicksort-based method is most likely the one that will be expected in a programming interview, it is interesting to explore a rather elegant linear-time deterministic algorithm posed by Manuel Blum (Turing Award winner), Robert Floyd (Turing Award Winner), Vaughan Pratt (helped found Sun Microsystems), Ronald Rivest (Turing Award winner), and Robert Tarjan (Turing Award winner).

It goes like this:

-

Break the input into groups of 5 elements. For example, the array [4, 3, 7, 5, 8, 1, 0, 2, 9, 6, …] would be broken up into [4, 3, 7, 5, 8], [1, 0, 2, 9, 6], and so on in linear time.

-

Find the median of each group in linear time - because finding the median of exactly five elements takes constant time.

-

Find the median of these medians recursively - let’s call it x. If we assume that the algorithm is indeed O(n), then this takes T(n/5).

-

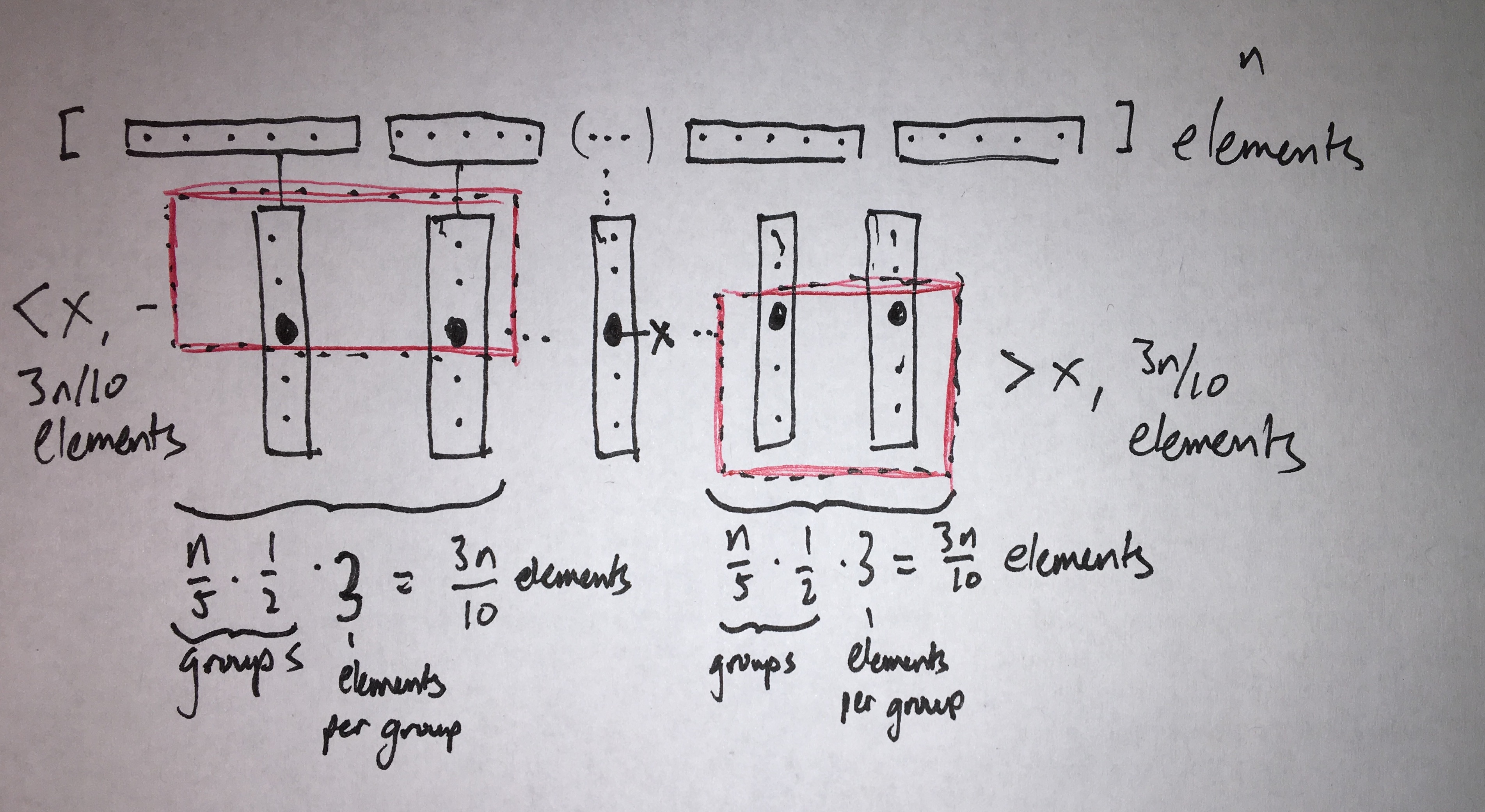

Construct L from all elements less than or equal to x and R from all elements greater than x, just like in quicksort or quickselect. 1/2 of the groups of 5 will have medians less than x, and 1/2 of the groups of 5 will have medians greater than x. Within each group where the median is less than x, the two smallest elements are less than the median and are therefore less than x. Likewise, for each group of 5 where the median is greater than x, the two largest elements are greater than the median and are therefore greater than x. Therefore, at least 1/2 (groups less than x) * 3/5 (elements less than x per group of 5 - the 3 comes from the two elements less than the median and the median itself) = 3/10 of the total elements are less than x, and likewise 3/10 of the total elements are greater than x - see the below picture for the intuition behind this.

This means that the larger half of the array is at most 7/10 the size of the original array. Therefore, this step takes T(7n/10), if we simplify matters and always analyze the larger half of the array - it is worst-case analysis, after all.

This means that the larger half of the array is at most 7/10 the size of the original array. Therefore, this step takes T(7n/10), if we simplify matters and always analyze the larger half of the array - it is worst-case analysis, after all. -

Recursively call median of medians on the half of the array that k lies in - again, if |L| >= k, then recur on L, if |L| = k - 1, then pick x, and if |L| < k - 1, then recur on R.

Runtime Analysis

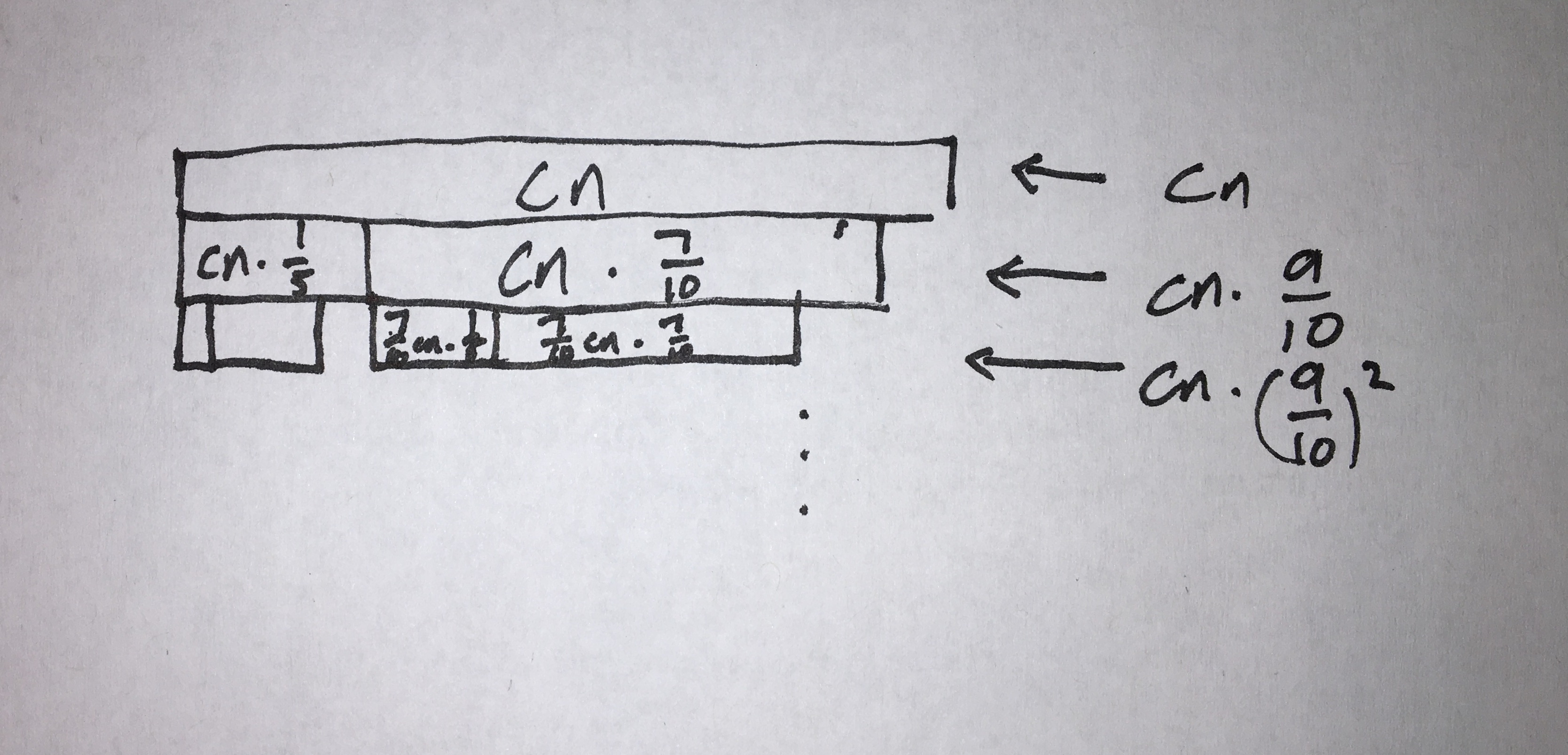

For the runtime analysis, it is a bit tricky to arrive at the desired O(n) bound without writing and solving the recurrence, but if we look at the fact that at each recursive step, it takes some O(n) work plus the recursive calls T(n/5) and T(7n/10), which, when “added”, equal 9n/10, which means that after each recursive call, the size of the input decreases geometrically, which means that our recurrence is big-O of the time of the first recursive call, O(n).

Formally, we can draw a brick diagram of runtimes and then show, with the aid of an infinite sum, that geometrically decreasing runtime per step is effectively a constant.

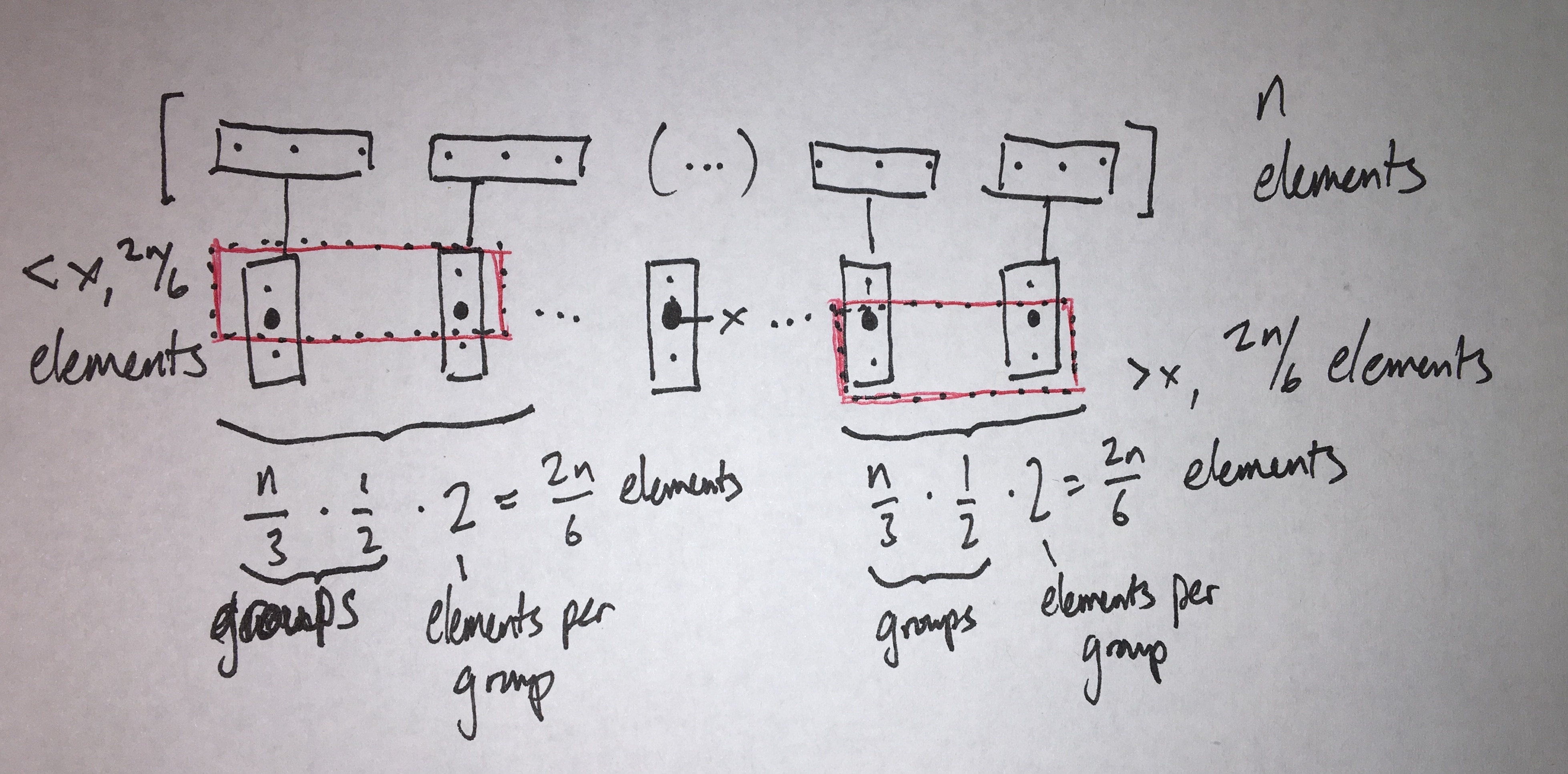

It is interesting to note that if we break the input into groups of three, we are unable to show the O(n) upper bound because the first recursive term in the recurrence becomes T(n/3) and the second becomes T(2n/3) - because we can guarantee that the median is greater than 2n/6 = n/3 elements, and therefore the larger half of the array is at most 2n/3 - which sum up to n and each recursive step is the same work as the last, and the recurrence is balanced rather than root dominated which gives us O(n log n) runtime.

Conclusion

In this post, we introduced the problem of selection and explained two algorithms that solve it: a randomized algorithm based on quicksort that finds the k-th element in O(n) expected work, and a deterministic algorithm that finds the k-th element in O(n) work always. We also did some runtime analysis with recurrences, a powerful tool to formally show tight runtime bounds for recursive algorithms that would be difficult or impossible to arrive at informally.