Algorithms - Double Binary Search

Welcome to the first of a series where I post a programming interview question and work through it, posting code and explanations of my approaches, pitfalls, and clever tricks! I may use different languages and compare the results if there are interesting or noteworthy differences, but I will generally use Python due to its brevity and ease of understanding. The focus here is on the algorithm, approaches, and clarity of code rather than any particular code finesse. Send comments or corrections to josh@jzhanson.com.

Note: time and runtime in the context of runtime analysis both mean work, which is how the algorithm takes to execute on a single processor, i.e. sequentially, as opposed to span, which is how long the algorithm takes if we assume infinite processors - span is the longest single branch of the recurrence tree, that is, the most work that has to be done by any single processor among our infinite processors. If the wording is ever ambiguious, I mean work.

Second note: the diagrams are pictures I took with my phone of the diagrams drawn on paper - once I figure out a good diagraming software, I’ll probably replace the pictures. But having pictures of hand-drawn diagrams actually adds a bit of character and humanity to these posts, which I like :).

Double Binary Search

or, Median of Two Sorted Arrays, or, kth-smallest

It’s trivial to find the median of a single sorted array A: just take the length of the array n and find A[n/2]. If you want to be fancy, you can find A[n/2] if the array is of odd length or the midpoint between or average of A[n/2 - 1] and A[n/2] if the array if of even length.

def median_simple(A):

n = len(A)

return A[n/2]

def median_fancy(A):

n = len(A)

if (n % 2 == 0): # array length is even

return (A[n/2 - 1] + A[n/2]) / 2

else: # array length is odd

return A[n/2]

But what if you wanted to find the median of two sorted arrays? It might seem straightforward at first, especially if all the elements of one array are less than all the elements of another array, e.g. [1, 2, 5, 7] and [15, 21, 33], but what if the arrays overlap, or even share elements? How would we find the median of, say, [2, 5, 7, 8] and [0, 3, 4, 6, 7, 9]?

Word on the street is that this is an essential question to know for Google coding interviews, and by word on the street, I mean word straight from the mouth of Professor Guy Blelloch in the lecture of 15-210: Parallel and Sequential Data Stuctures and Algorithms at Carnegie Mellon University taught under the School of Computer Science undergraduate program…

The problem

We define the median element of two or more arrays to be the median of the array formed when all the arrays are combined and sorted, preserving duplicates. For example, the median element of [2, 5, 7, 8] and [0, 3, 4, 6, 7, 9] would be 5. We define the kth-smallest element of two or more arrays to be element k + 1 of the array formed when all the arrays are combined and sorted, preserving duplicates. Using the above example, the 1st-smallest element would be 0 and the 4th-smallest element would be 4.

- Given two sorted arrays of equal size A and B, find the median element.

Input: two sorted arrays of equal size A and B whose elements are integers (but can be any other element for which there exists a total ordering).

Output: the median element of the array formed when both arrays are combined and sorted - if C is the sorted “union” preserving duplicates of A and B with length n, the median would be the element at index n/2 if n is even and n/2 + 1 if n is odd.

- Given two sorted arrays of unequal size A and B, find the median element.

Input: two sorted arrays of unequalequal size A and B whose elements are integers (but can be any other element for which there exists a total ordering).

Output: the median element of the array formed when both arrays are combined and sorted - if C is the sorted “union” preserving duplicates of A and B with length n, the median would be the element at index n/2 if n is even and n/2 + 1 if n is odd.

- Given two sorted arrays of unequal size A and B and an integer k, where k <= |A| + |B|, find the kth-smallest element of the two arrays. We use the bars | to denote the size of an array or the length of a string, so |A| is the size of A.

Input: two sorted arrays of unequal size A and B whose elements are integers (but can be any other element for which there exists a total ordering).

Output: the kth-smallest element of the array formed when both arrays are combined and sorted - if C is the sorted “union” preserving duplicates of A and B, the kth-smallest element would be element k+1.

Foray #1: Brute force

We will tackle 1 and 2 together while 3 is mostly left as an exercise.

A good place to start, in programming interviews, is always to talk through and explore the simplest, often brute force solution. It is almost never the correct solution, but doing so 1) prevents you from sitting there silently for several minutes thinking like a maniac and trying to come up with the perfect solution, 2) fills up the time and helps show your thought process to the interviewer, and 3) helps build intuition on the problem.

The simplest solution here is to combine both arrays into one big array, sort it, and then trivially find the median of that big array. Let n = |A| + |B|. If we use an implementation of arrays that allows appending in O(n) work and O(1) span and a decent (read: asymptotically optimal) sorting algorithm which runs in O(n log n) work and, if we’re picky about the parallelism of our algorithms, has O(log3 n) span cough mergesort cough, then this gives us a total work of O(n log n) and a total span of O(log3 n) span.

def double_median_naive(A, B):

C = A + B # in Python, + appends two lists

sort(C) # Python's list sort is mergesort

return C[len(C) / 2]

This isn’t optimal. Intuitively, it feels like we’re doing a lot more work than we need to; we’re merging and sorting both arrays when we really just need to determine the middle element. Also, do we really need to sort the big array again when both A and B are sorted?

I didn’t mention mergesort up there for nothing: if you’re sharp, then you read mergesort and immedialy thought “Why don’t we just merge A and B instead of appending and sorting?”

We merge A and B a la mergesort by starting a pointer at the beginning of both arrays, comparing the element under the pointer in A with the element under the pointer in B, and advancing the pointer of whichever element is smaller. When we get to the n/2-th element, where n is the sum of the lengths of A and B, we return that one. If we do this, then we actually cut down our work to O(n). However, interestingly, our span becomes O(n). Here, we see the trade-off between work and span in action: algorithms can often become more parallel in exchange for doing more, sometimes repeated, work.

def double_median_merge(A, B):

n = len(A) + len(B)

if (n == 0) return None

count_a = 0

count_b = 0

# upon loop termination, count_a and count_b will be on n/2-nd and n/2+1-st

while (count_a + count_b < n/2 - 1):

if (count_a == len(A)): # if at end of array A

count_b += 1

continue

elif (count_b == len(B)): # if at end of array B

count_a += 1

continue

if (A[count_a] < B[count_b]):

count_a += 1

else:

count_b += 1

if (count_a == len(A)):

if (n % 2 == 0): # if even number of elements

return (B[count_b] + B[count_b + 1]) / 2

return B[count_b]

elif (count_b == len(B)):

if (n % 2 == 0):

return (A[count_a] + A[count_a + 1]) / 2

return A[count_a]

else:

if (n % 2 == 0):

return (A[count_a] + B[count_b]) / 2

return A[count_a] if A[count_a] < B[count_b] else B[count_b]

Couple things to note here: we need to check for a couple edge cases, namely, what happens if one or both arrays are empty. Note that if one array is empty but not both, the count_a == len(A) or count_b == len(B) cover it but we need to return None if both arrays are empty. We also have a slightly-awkward loop counter with count_a + count_b < n/2 - 1, which is just to make sure that the final iteration makes the termination condition, which is that count_a and count_b will be on elements n/2 and n/2 + 1, not necessarily in that order. Also, depending on how you in particular code it, you might have to worry about when the arrays are both 1 element.

This works both for when the arrays are equal size and when the arrays are unequal size.

Foray #2: Divide and conquer

Now the next step takes a bit of a mental leap. If we think about what we know about the problem, we want to find a specific element out of sorted arrays, except we’re not looking for the element by id but by cardinality, or rank. A good option here to explore, after hearing the words sorted and find, would be some sort of binary search, even just talking about it can show the interviewer that you’re on the right track and can prompt them to give you a hint to set you in the right direction. You could also maybe arrive by the divide-and-conquer paradigm by going through the common algorithmic paradigms. For example, when I’m looking for some smarter algorithm, I first think to see if a greedy algorithm would work, then a divide-and-conquer one, then dynamic programming, then backtracking, and finally graph algorithms.

Anyways, if we think about how we can use binary search to find the median of two sorted arrays, let’s think about what binary search does. Binary search looks at the median of a single sorted array or subarray, compares it to the target element, and drops the lower half of the array if the target element is larger than the median, because the target will not occur in the lower half where all elements are less than the median, which is less than the target, and symmetrically for if the target is lower than the median.

def binary_search(A, target):

if (len(A) == 0): return False

mid = len(A) / 2

if (A[mid] == target):

return True

elif (A[mid] < target): # if median is less than target

return binary_search(A[mid+1:]) # syntax for all elements before mid

else: # if median is greater than target

return binary_search(A[:mid])

We’re comparing the median of the sorted array to something, and then dropping half of the array based on that…this is the part where you either have the flash of inspiration or your interviewer prods you to the flash of inspiration. What if we compare the medians of the two arrays?

Equal length

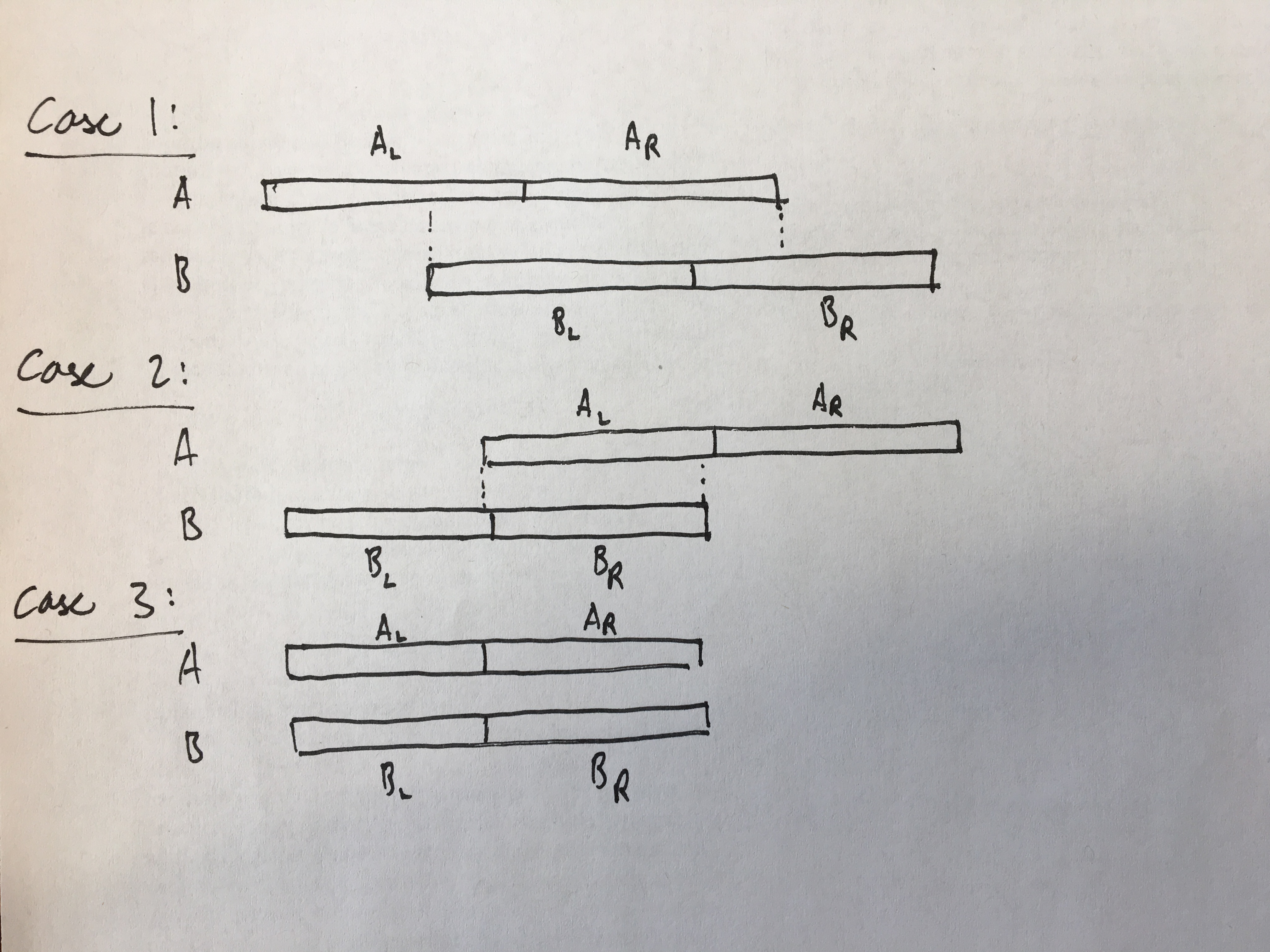

Let’s explore this, first if we assume the arrays are equal size. Simplifying assumptions are a great way to get a start on a problem and build intuition. If the arrays are equal size and we compare the medians, we have three cases:

-

If the median of A is less than the median of B, then we know that the true median has to be in the second half of A, AR or the first half of B, BL inclusive of the sub-medians.

-

If the median of A is greater than the median of B, then we know that the true median has to be in the first half of A, AL or the second half of B, BR, inclusive of the sub-medians.

-

If the median of A is equal to the median of B, then our job just got a lot easier! The median is either one of those medians.

The picture below should help illustrate the intuition behind these three cases.

Again, if it intuitively seems like we can immediately find the median of two equal length sorted arrays, take a moment to convince yourself why that isn’t true. Writing out a couple of examples might help.

Solution

def double_binary_search_eq_len(A, B):

if (len(A) == 0) and (len(B) == 0):

return None

if (len(A) == 1) and (len(B) == 1):

return (A[0] + B[0]) / 2

elif (len(A) == 2) and (len(B) == 2):

return (max(A[0], B[0]) + min(A[1], B[1])) / 2

mid_a = len(A) / 2

mid_b = len(B) / 2

if (A[mid_a] < B[mid_b]):

return double_binary_search_eq_len(A[mid_a:], B[:mid_b-1])

elif (A[mid_a] > B[mid_b]):

return double_binary_search_eq_len(A[:mid_a-1], B[mid_b:])

else:

return A[mid_a]

The first if/elif statement is the base case - if both arrays are length 2, then the “median” of each is the first element always, and we could get stuck in a loop where the arrays aren’t actually shortened at each step.

This takes O(log n) work and span because we are chopping off roughly half of our total input size at each iteration, and because we only have one recursive call, there is no parallizibility.

Unequal length

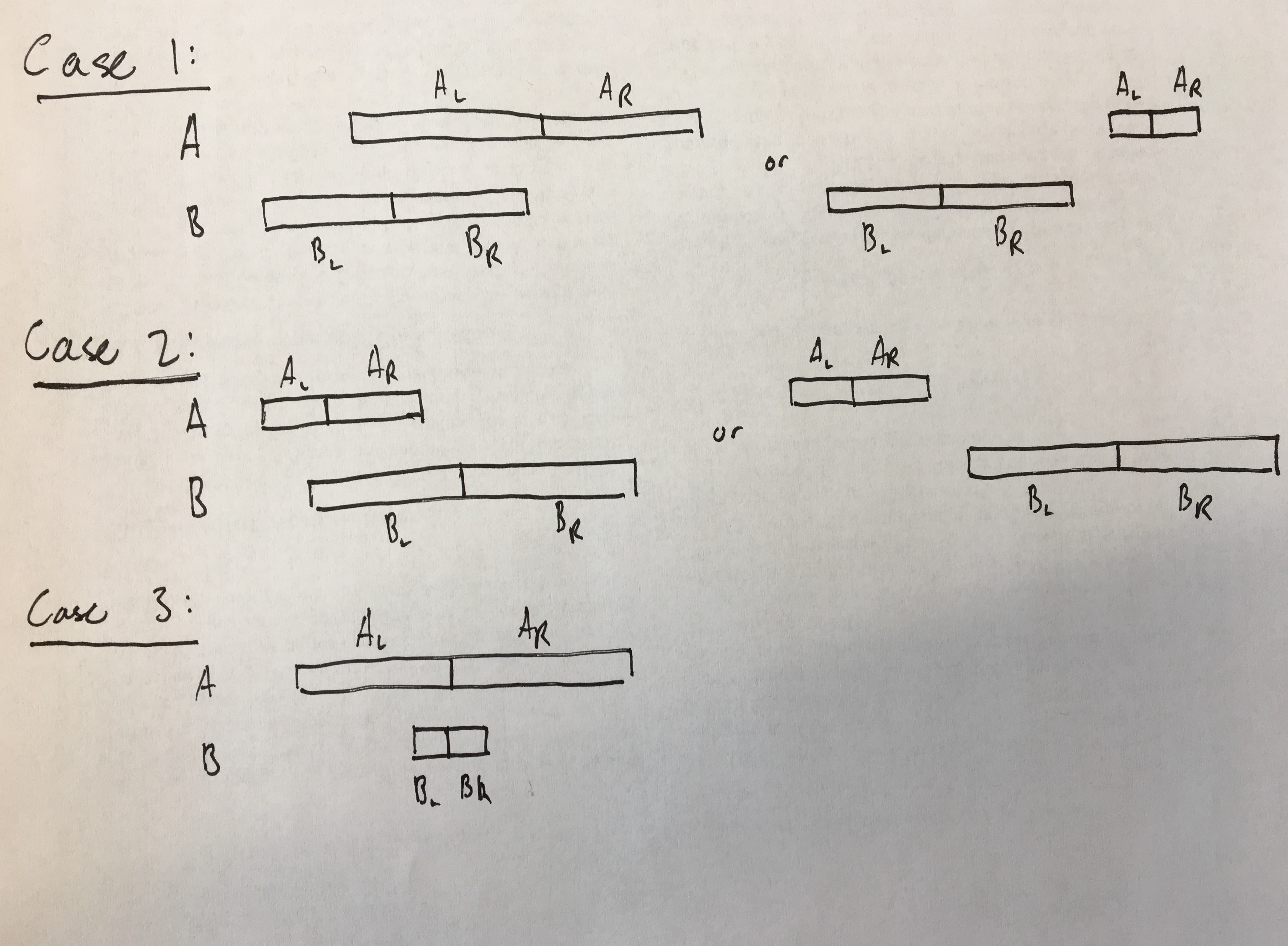

Now let’s take this one step further. What if our two arrays A and B are of unequal length? There’s not actually that much different about our algorithm. We still compare the medians of both arrays, but we have to make some different assumptions about how we can “chop” off parts of our arrays. However, we also have the information about the lengths of the arrays to help us out. Let’s also assume, for simplicity, that |A| < |B|. If A is larger than B, we can just swap the arrays - the logic is symmetric.

We again have a couple cases:

-

If the median of A is greater than the median of B, then we can drop all of the second half of A, AR. Additionally, we can drop that many elements from the first half of B, BL, but we cannot always drop all of BL.

-

Symmetrically, if the median of A is less than the median of B, then we can drop all the first half of A, AL. Additionally, we can drop that many elements from the second half of B, from BR.

-

If the median of A is equal to the median of B, then we can do either of the above two cases. Let’s just use the second one here. Note that if you would like to make this a separate base case where you compare the medians and perhaps also the neighboring elements to the medians if the arrays are both even or both odd - for example, the median of both [0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10] and [1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 9] are both 4 but the median of the merged arrays is 5.

Another reason that interviewers like this problem is that there are a lot of base cases to account for, especially with arrays of unequal length. We can reduce them by forcing A to be shorter than B, of course, but there are still a couple we have to account for.

Solution

def double_binary_search(A, B):

if (len(A) == 0):

if (len(B) == 0):

return None

return B[len(B) / 2] # if A is empty, return median of B

if (len(A) == 1) and (len(B) == 1):

return (A[0] + B[0]) / 2 # if one element in both arrays

if (len(A) == 1):

if (len(B) % 2 == 0):

if (A[0] < B[len(B) / 2]):

return B[len(B) / 2]

elif (A[0] > B[len(B) / 2]) and (A[0] > B[len(B) / 2 + 1]):

return A[0]

elif (A[0] > B[len(B) / 2 + 1]):

return B[len(B) / 2 + 1]

else:

if (A[0] < B[len(B) / 2 - 1]):

return (B[len(B) / 2 - 1] + B[len(B) / 2]) / 2

elif (A[0] > B[len(B) / 2 - 1]) and (A[0] < B[len(B) / 2]):

return (A[0] + B[len(B) / 2])

elif (A[0] > B[len(B) / 2]) and (A[0] < B[len(B) / 2 + 1]):

return (A[0] + B[len(B) / 2 + 1])

else:

return (B[len(B) / 2] + B[len(B) / 2 + 1]) / 2

elif (len(A) == 2):

if (len(B) == 2):

return (max(A[0], B[0]) + min(A[1], B[1])) / 2

elif (len(B) % 2 == 0):

# ...

else:

mid_a = len(A) / 2

mid_b = len(B) / 2

if (A[mid_a] > B[mid_b]):

return double_binary_search(A[:mid_a+1], B[mid_a:])

else:

return double_binary_search(A[mid_a:], B[:len(B)-mid_a])

There’s a lot of base cases that don’t do much but get in the way of the core idea. The rest of the |A| = 2 cases are fairly similar to the first couple. They mostly just boil down to examining cases and then finding the median of more than two elements.

Conclusion

That’s the end of the very first algorithms post, and boy was it hefty, with over 2600 words. I hope this has been helpful - it was certainly helpful for me to get all my thoughts on this particular problem, which have been jangling around in my head for weeks now, down and clear. And it’s definitely a work in progress - I intend to finish writing the code and thoroughly test it and post a link to it on my GitHub. Send any comments or corrections to josh@jzhanson.com. Cheers!

2022-11-13 Bonus - thanks Aleksandar Bosnjak!

We reasoned about the time complexity of the algorithm with our discussion of work and span, but what’s the space complexity of the code we wrote? How much space will our recursive calls take?

Click to see the answer

O(n) (where n is the size of the input lists A and B)! Why? Because every time we make a recursive call of double_binary_search, we're creating new Python lists! double_binary_search(A[:mid_a+1], B[mid_a:]) and double_binary_search(A[mid_a:], B[:len(B)-mid_a]) both create two new lists. Granted, those lists are each half the size of the starting lists, but the infinite sum (1/2 + 1/4 + ...) still adds up to 1. Our sum isn't exactly infinite. In fact, we only have O(log n) levels. But that still means that we're using O(n) space, which sucks for a searching algorithm.How can we improve this code?

Click to see the answer

We can rewrite the function double_binary_search to take four additional arguments: the "start" and "end" indexes of A and B for each function call. Then, instead of slicing A and B and passing the sliced lists as arguments in a recursive call, we pass A and B, and the start and end indexes. This is a straightforward change, but it's also fairly involved and left as an exercise to the reader. :) How can you compute the mid indexes cleanly? Are there any additional special cases by rewriting the code this way? And are there any other improvements you can make to the code? After you revise double_binary_search to pass start and end indexes as arguments, you can be sure that you really understand the solution. Happy coding! :)Here’s a quick way to check that Python does indeed create new lists when slicing and reassigning (via passing as an argument) but keeps the same list when passing the original list as an argument.

x = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

def recursive(x):

print('at start address', id(x), x)

if len(x) == 0:

return

x[0] = -1

print(x, 'before recursive')

recursive(x[1:])

print(x, 'after recursive')

recursive(x)

Running this script, we see the output

at start address 140496339661248 [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

[-1, 2, 3, 4, 5] before recursive

at start address 140496350644224 [2, 3, 4, 5]

[-1, 3, 4, 5] before recursive

at start address 140496350709184 [3, 4, 5]

[-1, 4, 5] before recursive

at start address 140496350709120 [4, 5]

[-1, 5] before recursive

at start address 140496350709056 [5]

[-1] before recursive

at start address 140496350708992 []

[-1] after recursive

[-1, 5] after recursive

[-1, 4, 5] after recursive

[-1, 3, 4, 5] after recursive

[-1, 2, 3, 4, 5] after recursive

As we can see, the addresses of each list x are different. Also, we can see in the “after recursive” print outs that each list x in the previous function call is not changing, only the local copy of x in each function call.

Now look at this other test script

def recursive_keep(x, depth=0):

print('at start depth', depth, 'address', id(x), x)

if depth == 5:

return

x[depth] = -1

print('x before recursive_keep', x)

recursive_keep(x, depth=depth + 1)

print('x after recursive_keep', x)

recursive_keep(x)

Running this script gives us the output

at start depth 0 address 140612129747392 [-1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

x before recursive_keep [-1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

at start depth 1 address 140612129747392 [-1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

x before recursive_keep [-1, -1, 3, 4, 5]

at start depth 2 address 140612129747392 [-1, -1, 3, 4, 5]

x before recursive_keep [-1, -1, -1, 4, 5]

at start depth 3 address 140612129747392 [-1, -1, -1, 4, 5]

x before recursive_keep [-1, -1, -1, -1, 5]

at start depth 4 address 140612129747392 [-1, -1, -1, -1, 5]

x before recursive_keep [-1, -1, -1, -1, -1]

at start depth 5 address 140612129747392 [-1, -1, -1, -1, -1]

x after recursive_keep [-1, -1, -1, -1, -1]

x after recursive_keep [-1, -1, -1, -1, -1]

x after recursive_keep [-1, -1, -1, -1, -1]

x after recursive_keep [-1, -1, -1, -1, -1]

x after recursive_keep [-1, -1, -1, -1, -1]

This time, the address of the list x is the same in each recursive call. Not only that, the list x in each stack frame is changing as we change values in x to -1.